Hanoi can easily be a shopping mecca for souvenir-seekers, but the country’s capital offers so much more for both art lovers and accidental tourists.

A typical walk around Hanoi would lead travelers to Hoan Kiem Lake to take in the sights and catch a glimpse of its centenary “great grandfather” turtle. If you’re lucky, locals say, you might see it when it lifts its head above the water, perhaps as a hint of showmanship. (Some locals are not aware that the legendary creature passed away in January 2016). The soles of your feet could also bring you to the nearby red Huc bridge, which runs through the center of the famous moss-green lake.

The way there is a convoluted, lovely mess whether you’re coming from the Old French quarters or the Silk Road of Hang Gai. For the average pedestrian, Hanoi’s streets—from Ly Quoc Su to Hang Be—are decidedly a maze of sort. Every turn is a welcome surprise. There’s always a souvenir seller, a silk merchant, or a bun cha eatery, as well as a shrine, a t-shirt maker, and the occasional counterfeit goods seller. (Just don’t get hit by mo-peds while crossing the street.)

#AD: Follow others’ footsteps and make most of your stay in Vietnam. Learn more about how to travel and teach English in Vietnam here.

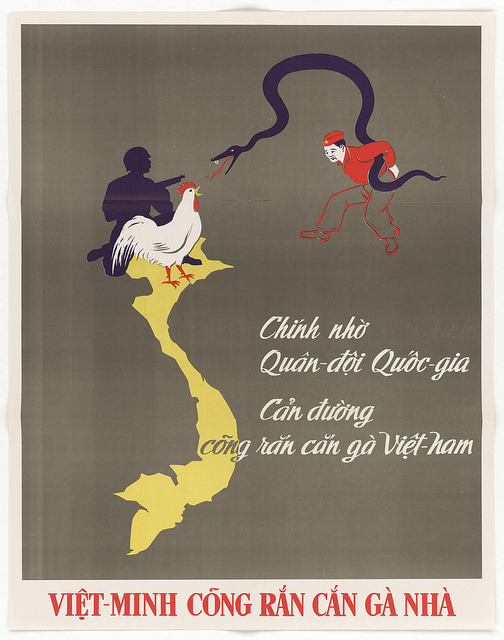

A few blocks away, one can find an Old Propaganda Posters shop along Ly Quoc Su, across famed coconut pastries shop, Joma Bakery Cafe. As far as Vietnamese stores go, the shop is comparable to a stall, but don’t let its size fool you. The shop hosts piles of art prints, from replicas of OBEY founder and street artist Shepard Fairey’s Make Art Not War, to the “real deal” propaganda prints of 1940s and 1970s. Its walls are also adorned with motivational posters of another kind: one on ousting American forces, and another on hero worshiping Uncle Ho—Ho Chi Minh, to the rest of the world.

Propaganda posters are representative of Vietnam’s patriotic past, present and future; they line the streets during national events, or for no special reason at all. They call to mind pop art and kitsch, utilizing bold reds, blue and yellows, as well as unequivocal symbols such as the hammer and sickle, which signify the long-standing Communist ties between Russia and Vietnam.

In one poster, a red, closed fist with a gold star splits a U.S. B-52 in half, which, perhaps embodying the intense patriotism and animosity Vietnam had for the U.S. during the war. (One local, a former television presenter, once remarked to this writer that the French and Americans “came and we drove them out.”) Others portray the Vietnamese way of life, such as a woman dressed in traditional clothing and transferring milled rice to a sack, or children holding hands in a circle.

Today’s propaganda posters are stylistically updated, but traces of earlier traditions are noticeable. Regardless, they serve the same purpose: to remind locals of their duty to the homeland, and uphold good values passed on from generations to generations. “People looked to propaganda posters for a sense of direction,” historian and National Assembly deputy Duong Trung Quoc, told Channel News Asia once. The medium is not without challenges, however. Quoc criticized the decline of the art form, describing new output as “boring and repetitive” due to “lack of investment in logical thinking,” according to the news website.

Oil paintings are also on sale for meandering tourists keen on exploring the city on foot. The pricier ones find home in the galleries, while those made by local artisans and the every man are displayed on the streets. Paintings of everyday objects, animals (yes, including cats) and scenes of traditional life in Vietnam are often portrayed in the paintings that cost anywhere between $30 and $200. Tourists are free to haggle to their heart’s content; but as in anywhere in the world, being considerate of local wages and living conditions are encouraged. The average national salary in the country is also somewhere around $150 and Vietnam art requires resources, as well.

Authenticity seemed to be an issue for some tourists in Hanoi, especially when it comes to prints, although presumably, most tourists wouldn’t mind. Some buyers on the web pointed out that the prints they bought were fake, after being made to believe that they were buying authentic reprints. Some favor one store over the other; the Hanoi Gallery along Hang Bac being a favorite among tourists. While some are understandably concerned about the quality of the prints or paintings they bought, one thing’s for sure: the medium of expression is a testament that art is a powerful way to change minds and launch an inquiry into current values, in an era of fake news and sensationalism.

Featured Image Credit: Prince Roy/Flickr